The material is divided into five webpages linked from the navigation bar above: (1) on Pedrón's personal and family history and relations; (2) information extracted from Marine-Guardia documents; (3) EDSN letters and correspondence; (4) the IES testimonies; and (5) published materials and other sources. The sixth icon above takes you back to this homepage. I thank José Mejía Lacayo for his help in developing this page, and Walter Castillo Sandino for kindly providing key photographs of Gral. Pedro Altamirano and his family. A Jinotega native, 57 years old when he joined with Sandino in late 1927, large and thick in physique, and functionally illiterate, Pedrón showed an unparalleled ability to elude his pursuers and wage a ruthlessly effective guerrilla campaign. From the beginning to the end of the war, and despite relentless efforts, the Marines-GN never so much as glimpsed him, except in photographs. Occasionally nipping at his rear guard or flanks, they never engaged his entire band in combat, despite repeatedly combing his area of operations with dozens of patrols led by the most experienced field officers. Remarkably, he was the only Sandinista to remain active in the field after Sandino's assassination in February 1934.

For nearly four years

after the Guardia had utterly crushed every other

remnant of the EDSN, Pedrón and the remnants of his

band eluded all detection, until he was finally betrayed

and killed in late 1937. Indeed, some former

rebels, interviewed in the 1980s, attributed his

extraordinary abilities to telepathy, clairvoyance, or

some other special magical powers. And indeed there are

times when his ability to avoid all detection does seem

to border on the magical.

In sum, in the Marines' sustained six-year effort to secure actionable intelligence on Sandinista General Pedro Altamirano, everything failed.

His uncompromising hatred of the US intervention, the US Marines, and Yankees in general was paralleled by what seems to have been an equally visceral hatred and disdain of wealthy Nicaraguan property owners. Consider the following letter to one property-holder in the Jinotega coffee district of November 1930, a few months after Sandino's return from Mexico:

Through this process of what I call "patriotic plunder" — built on the longstanding Segovian practice of issuing "guarantees" (what in the USA during this same period would be called "protection money") — Pedrón systematically siphoned resources from Matagalpa-Jinotega property owners and raised money for the Defending Army, for arms, ammunition, medicine, supplies. Many property owners agreed to pay and were thereby "guaranteed". Many others refused and instead sought Marine-Guardia protection. The Marines-Guardia, in turn, routinely denied requests from property owners for protection from Pedrón and other Sandinista "bandits". The results were . . . very complicated. And often very violent.

Note that Pedrón

uses the word "property" three times in this

threatening letter — the last time in a voice that seems

marked by utter contempt. There are suggestions in

the documents that he was once a property owner himself.

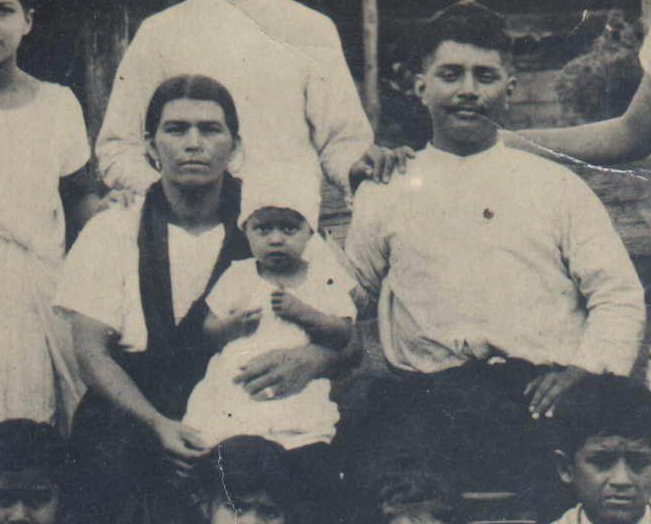

The first known photograph of Pedro Altamirano, below,

shows him, his wife Señora María Pio Altamirano de

Altamirano, and ten children posing for the camera, all

well dressed, with the girls wearing nice shoes,

stockings, and dresses. The family looks happy, well fed, and relatively prosperous.

The year is not known, but it looks to be at least ten

years before the wartime photos — perhaps as early as

the mid-1910s. My best guess is around 1915.

The close-up below shows Pedro Altamirano with half-closed, relaxed eyes and a face that exudes contentment and pride in his family. His wife María looks equally happy, quietly dignified, and immensely proud of her family.

The small child at center, wearing a baptismal bonnet, and the nine other children and young adults ranging in age from perhaps 25 to 3 years old, suggests a formal photograph taken after church service on the occasion of the child's baptism. In the opinion of José Mejía Lacayo, the five children seated at front are the grandchildren of Pedro and María Altamirano. His best estimates of their ages are superimposed on the photo below:

The entire scene, including the tile-roof house in the background, suggests that Pedro Altamirano was, at this point in his life, a relatively well-to-do property owner — a member of Las Segovias' small but growing rising middle class. Below are sepia-toned closeups of the four grown children in the rear and the couple at center:

I suspect these were the "golden years" of his life — before he lost his property and became a full-time outlaw. Based on his later behavior, my hunch is that he was somehow swindled or cheated out of his property by a more powerful and wealthier landowner — maybe a native Nicaraguan, more likely European or North American — and as a result he came to harbor an abiding hatred of the law and propertied landowning elites, native and especially foreign. Many of his actions seem to bear the scar of some profound injustice relating to the law, property, and foreigners. According to the memoirs of Jinotega native Simeón Rizo Gadea (Nicaragua en mis recuerdos, 1985), the young campesino Pedro Altamirano lived with his family at the foot of Saraguasca Mountain on a hacienda owned by one Teodoro Martínez — milking cows, crafting leatherware, and tending horses. One day Sr. Martinez noticed the mane of one of his ponies had been cut and blamed young Pedro. He notified the authorities and young Pedro was thrown in jail, where he languished for months. Pedro escaped, was recaptured, and escaped again, promising himself that he would never be recaptured, and thus became a smuggler of tobacco and firearms to and from Honduras. Henceforth, the story goes, he never slept indoors and became intimately familiar with all the Segovian mountains. Another account (published on the official web page of the Nicaraguan Army) holds that Pedro Altamirano became a maker and seller of cususa or cane liquor, and got into trouble with the Resguardo de Hacienda (tax collectors) for making illegal moonshine and evading taxes, and thus became an outlaw. Maybe his later antipathy to alcohol stems from this period? In fact we know almost nothing about the first 50 or so years of his life. We do know the names of four of the couple's sons — Melecio, Candelario, Chano, and Pedro Ramón — and of one of their daughters — Victorina. In 1930 Victorina was being courted by Sandinista soldier Fernando Mora Dávila, as seen in a number of their surviving love-letters. We also know that on 20 August 1930, three of his children were killed in an encounter with the Marines and Guardia (Encarnación, Victorina, and an unnamed little girl), and two others wounded (Melecio and Pedro Jr., known as Pedrito). A fragment of a letter from Sandino dated 25 August 1930 reads: On the 20th of August in a place called El Balsamo, there was an encounter between the family of General Pedro Altamirano and the enemy. The fight was short but bloody. Dying in the exchange of shots was the eldest son of General Pedro Altamirano, whose name was Encarnación, of the same surname. Also killed was a little girl and a daughter-in-law of the same General, and in addition three of his children were wounded whose names were Victorina, Melecio, and Pedro Jr. A few days later Victorina died as a result of the wounds. On the part of the enemy there were seven casualties, but they remained in the field. The event is confirmed in a patrol report of 26 August 1930 by G.N. Captain G. F. Good ("Contact with bandits on 20 August, 1930"). The report notes that "one Jefe, between 25 and 30 years of age, light coffee color, small brown eyes, slightly flattened nose, high cheek bones, black hair, height 5 ft. 9 in., weight about 145 lbs. dressed in white clothes with black pin stripe, gray felt sombrero with broad red and black band and high laced boots was killed instantly and left on the field by the bandits. This man is thought to be the son of Pedron Altamirano from a comparison with the picture found among captured papers." The deaths of his children in August 1930 hit Pedrón hard. On 10 November 1930, in a letter demanding a contribution from British coffee plantation owner William Hawkins in Matagalpa, Pedrón made known his seething anger and desire for vengeance: It will not be strange that at any day we arrive at your hacienda. Make ready for me two thousand córdobas. Do not propose to turn over the money without the penalty of your life. I know that you have Marines and Guardia but to me it is of no importance. I understand this with indifference because now I go seeking vengeance for the blood of my children. This much I tell you.

Above: Close-up of Pedrón's signature, from a dictated letter to Capitán Sabas Manzanares, 25 June 1930, RG127/38/31. Nicaraguan memories of Pedrón remain strong to this day. For instance, the FSLN's decision to rename the hospital in La Trinidad "El Hospital Pedro Altamirano" in the early 1980s sparked considerable controversy. I am also told that many of the stories & poems generated by old people during the early 1980s in the Sandinistas' award-winning National Literacy Campaign (Cruzada Nacional de Alfabetización), now housed in El Museo de Alfabetización in Managua, took Pedrón as their subject. This would seem a fruitful and mostly untapped resource for learning more about the social constructions of memory around his person and legacy. Web-accessible accounts of General Pedro Altamirano can be found in an article by Eduardo Cruz and Amalia Morales in La Prensa of 22 February 2015, and on the website of the Ejército de Nicaragua, where a brief biography can be found in the section on national heroes. Remarkably, there exists no biography or scholarly study of Sandinista General Pedro Altamirano, in English or Spanish. So watch these pages for the accumulation of evidence relating to the life & times of this fascinating & puzzling character. The weakest part of the collection to be housed here concerns his early life and family history. For instance, his first appearance in the documentary record, to my knowledge, came in November 1927, when he signed two short messages as "Captain Pedro Altamirano" (see Cartas y Correspondencia). By this time he was allied with Sandino and his Ejército Defensor, officially founded two months earlier. Except for the photograph above provisionally dated to around 1915, and the second-hand account related by Simeón Rizo Gadea, the first 50 or so years of his life remain shrouded in mystery. So if any readers have any information on his life & times before November 1927, your help would be much appreciated.

Above: Pedrón at left (marked "1"), machete strapped to his belt, with EDSN Gen. Ismael Peralta ("2") at right. No date. From the collection of Walter C. Sandino.

Above: Photo of Sandino and Pedrón inspecting EDSN troops. No date. From the collection of Walter C. Sandino. A close-up of Sandino and Pedrón appears below:

Above: Revolver reputedly used by one of Pedrón's relatives during the war against the Marines, housed in the Museo del Café at La Hacienda Selva Negra, Matagalpa, Nicaragua. Photo by the author, July 2010.

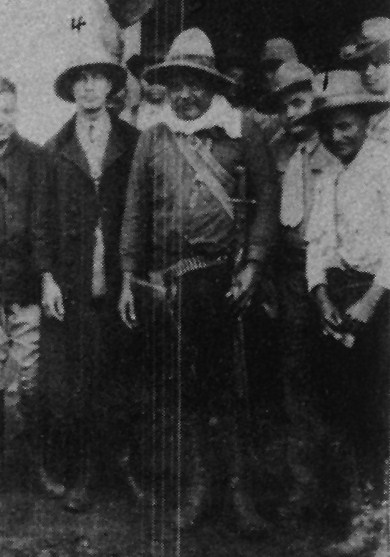

The most well-known and widely circulated photograph of Pedrón, in San Rafael del Norte during the rebels' disarmament following the provisional peace accords of February 1933, to which he was viscerally opposed.

|

a.jpg)

.jpg)

a.jpg)

b.jpg)